Table of Contents

- The Independent Dance of Chromosomes

- Principle of Independent Assortment

- A Tale of Two Traits

- Gamete Formation: The Shuffle Begins

- Predicting Offspring: A Probabilistic Approach

- The Probability Playbook

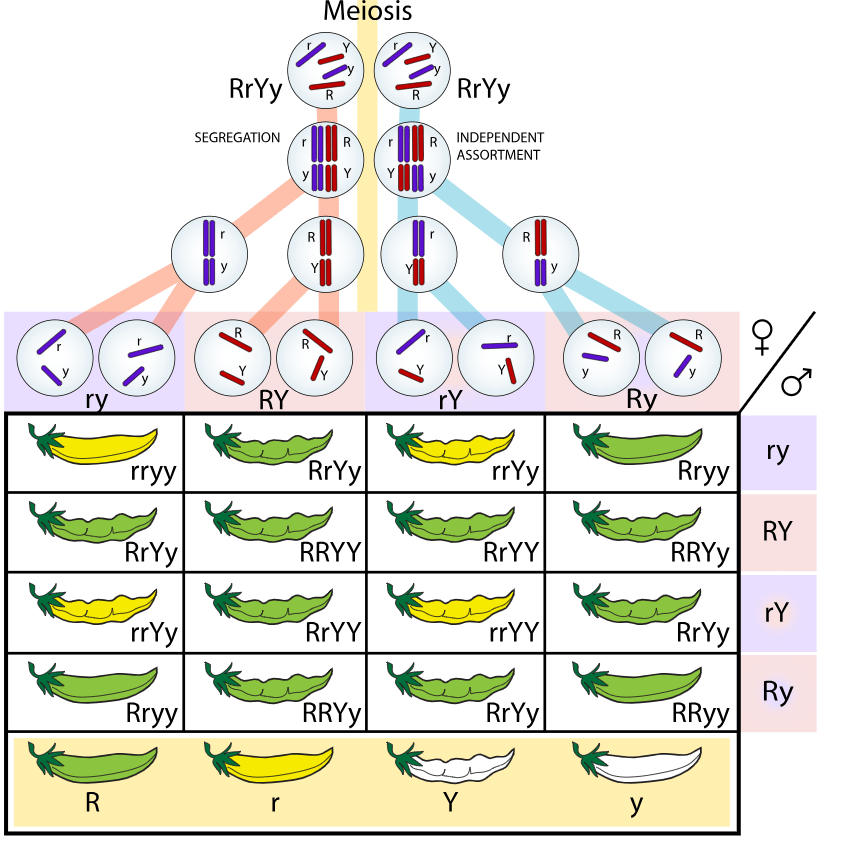

- The Punnett Square Puzzle (Dihybrid Cross)

- Here’s how it works, step-by-step

- Example: Pea Plant Color and Height

- Constructing the Punnett Square

- Summary

- The Significance of the Shuffle

- What is a Phenotype?

- Significance of Phenotype

- Will the Phenotypic Ratio Remain Constant in the 3rd and 4th Generations?

- Summary

- Beyond the Basics

- In Conclusion

We often marvel at the diversity of life around us, but have you ever stopped to consider the intricate mechanisms that drive this variety? One of the most fascinating aspects of genetics is how traits are inherited and combined in new ways during sexual reproduction. This blog post delves into the concept of independent assortment, a fundamental principle that explains how genes located on different chromosomes shuffle and recombine, contributing to the unique mix of characteristics we see in offspring.

The Independent Dance of Chromosomes

Imagine a pair of dancers, each with their own choreography. As they move across the dance floor, their steps are independent – one’s movements don’t dictate the other’s. This is much like how genes located on different chromosomes behave during meiosis, the cell division process that creates sperm and egg cells.

Principle of Independent Assortment

This principle of independent assortment, first discovered by Gregor Mendel, states that the alleles (different versions of a gene) for one trait segregate into gametes independently of the alleles for another trait. In essence, the inheritance of one characteristic doesn’t influence the inheritance of another when the genes controlling those traits reside on separate chromosomes.

A Tale of Two Traits

Let’s illustrate this concept with an example. Consider two traits, Trait T and Trait S, each controlled by a gene located on a different chromosome. Imagine a parent with the genotype TtSs, meaning they carry one dominant allele (T) and one recessive allele (t) for Trait T, and one dominant allele (S) and one recessive allele (s) for Trait S.

Gamete Formation: The Shuffle Begins

When this parent produces gametes (sperm or eggs), the alleles for T and S will assort independently. Think of it like shuffling a deck of cards – the arrangement of one suit (Trait T) doesn’t affect the arrangement of another suit (Trait S). This independent assortment leads to four possible combinations of alleles in the gametes:

- TS

- Ts

- tS

- ts

Predicting Offspring: A Probabilistic Approach

Now, let’s envision what happens when two parents with the genotype TtSs reproduce. There are two primary methods for predicting the genetic makeup and observable traits (phenotypes) of their offspring:

The Probability Playbook

We know each parent has a 50% chance of passing on either the T or t allele for Trait T, and similarly for Trait S. Using basic probability, we can calculate the probabilities of the offspring’s genotypes:

- For Trait T:

- TT: (1/2) * (1/2) = 1/4

- Tt: (1/2) * (1/2) + (1/2) * (1/2) = 1/2

- tt: (1/2) * (1/2) = 1/4

- For Trait S:

- SS: (1/2) * (1/2) = 1/4

- Ss: (1/2) * (1/2) + (1/2) * (1/2) = 1/2

- ss: (1/2) * (1/2) = 1/4

To determine the probability of a specific combination of traits (e.g., an offspring with genotype TtSs), we multiply the individual probabilities:

- Probability of TtSs: (Probability of Tt) * (Probability of Ss) = (1/2) * (1/2) = 1/4

The Punnett Square Puzzle (Dihybrid Cross)

- Dihybrid Cross: A dihybrid cross involves mating two individuals who are heterozygous for two different traits. These individuals will both express the dominant phenotype for each of the traits. The purpose of the dihybrid cross is to observe the phenotypic ratios in the offspring, typically resulting in a 9:3:3:1 ratio when the genes are unlinked.

- Heterozygous

Definition: Heterozygous means an individual has two different versions (alleles) of a gene, one inherited from each parent. These different alleles code for the same trait but may result in a different expression of it.

Example: If ‘B’ represents a dominant brown eye allele and ‘b’ a recessive blue eye allele, then an individual with the genotype ‘Bb’ is heterozygous for eye color. This person would have brown eyes because the B allele is dominant over the b allele. - Homozygous

Definition: Homozygous means an individual has two identical versions (alleles) of a gene, one inherited from each parent. Both alleles at the same gene locus are the exact same copy of a certain gene.

Example: An individual with two brown eye alleles (‘BB’) is homozygous dominant, and an individual with two blue eye alleles (‘bb’) is homozygous recessive. They both are homozygous for eye color, but one is homozygous dominant and the other one is homozygous recessive. - Alleles: Alleles are different versions of a gene, for example, “B” could be an allele for brown eyes, while “b” could be an allele for blue eyes.

- Genotype: Genotype is the combination of alleles an organism possesses, for example, “TtSs” is a genotype where the organism is heterozygous for two different traits.

A Punnett square is a tool used in genetics to predict the possible genotypes (genetic makeup) and phenotypes (physical traits) of offspring from a cross between two parents. When we consider two traits at the same time, it’s called a dihybrid cross. This requires a larger Punnett square to account for the increased number of possible gamete combinations.

Here’s how it works, step-by-step

- Identify the Traits and Alleles:

- A trait is a specific characteristic. Now, we’ll be looking at two traits.

- Alleles are different forms of a gene that control a trait.

- We use letters to represent alleles:

- Capital letters (e.g., “B”, “T”) typically represent dominant alleles.

- Lowercase letters (e.g., “b”, “t”) represent recessive alleles.

- Determine the Parental Genotypes:

- The genotype is the specific combination of alleles an individual has for the two traits (e.g., BbTt, BBtt, or bbTT).

- Homozygous means the individual has two identical alleles for a specific trait (e.g., BB or bb, TT or tt).

- Heterozygous means the individual has two different alleles for a specific trait (e.g., Bb or Tt).

- Determine the Possible Gametes from Parental Genotype:

- The gametes are all the possible combination of the traits. For two traits, each gamete will have one allele for each of the traits.

- Set Up the Punnett Square:

- For a dihybrid cross (two traits), we need a 4×4 grid (16 boxes total).

- Write the possible gametes from one parent along the top of the grid.

- Write the possible gametes from the other parent along the left side of the grid.

- Fill in the Grid:

- Combine the alleles from each row and column to fill in each box of the grid. Each box represents a possible offspring genotype.

- Analyze the Results:

- Count the number of times each genotype appears in the grid.

- Determine the probability (or percentage) of each genotype occurring in the offspring.

- Determine the phenotype of each genotype (considering which alleles are dominant).

Example: Pea Plant Color and Height

Let’s say we’re looking at two traits in pea plants:

- Trait 1: Flower Color

- Alleles:

- P = Purple flowers (dominant)

- p = white flowers (recessive)

- Alleles:

- Trait 2: Plant Height

- Alleles:

- T = Tall plants (dominant)

- t = short plants (recessive)

- Alleles:

Let’s cross two heterozygous parents for both traits (PpTt x PpTt). This means each parent has one purple-flower allele, one white-flower allele, one tall-plant allele, and one short-plant allele.

Constructing the Punnett Square

- Parental Gametes: Each parent (PpTt) can produce four types of gametes: PT, Pt, pT, pt.

- Punnett Square:

| PT | Pt | pT | pt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | PPTT | PPTt | PpTT | PpTt |

| Pt | PPTt | PPtt | PpTt | Pptt |

| pT | PpTT | PpTt | ppTT | ppTt |

| pt | PpTt | Pptt | ppTt | pptt |

- Explanation of the Table:

- The top row has the gametes of one parent, the leftmost column has the gametes of the other parent.

- Each internal square is filled by combining the gamete on the same row and the gamete on the same column.

- Genotype Combinations:

- PPTT: 1 box (homozygous dominant for both traits)

- PPTt: 2 boxes (homozygous dominant for color, heterozygous for height)

- PPtt: 1 box (homozygous dominant for color, homozygous recessive for height)

- PpTT: 2 boxes (heterozygous for color, homozygous dominant for height)

- PpTt: 4 boxes (heterozygous for both traits)

- Pptt: 2 boxes (heterozygous for color, homozygous recessive for height)

- ppTT: 1 box (homozygous recessive for color, homozygous dominant for height)

- ppTt: 2 boxes (homozygous recessive for color, heterozygous for height)

- pptt: 1 box (homozygous recessive for both traits)

- Phenotypes (Physical Appearance):

- Purple, Tall: (PPTT, PPTt, PpTT, PpTt) = 9 boxes

- Purple, short: (PPtt, Pptt) = 3 boxes

- white, Tall: (ppTT, ppTt) = 3 boxes

- white, short: (pptt) = 1 box

- Phenotype Ratio

- 9:3:3:1

- Probabilities

- Purple, Tall: 9/16

- Purple, short: 3/16

- white, Tall: 3/16

- white, short: 1/16

Summary

In this dihybrid cross, the Punnett square shows us that when crossing two plants that are heterozygous for flower color and plant height (PpTt), we get a variety of offspring genotypes and phenotypes. We see a 9:3:3:1 phenotypic ratio, meaning:

- 9/16 of the offspring will be purple and tall.

- 3/16 will be purple and short.

- 3/16 will be white and tall.

- 1/16 will be white and short.

The Punnett square makes it easy to see how the two traits are inherited independently and how different combinations of alleles can lead to different physical characteristics in the offspring.

The Significance of the Shuffle

Independent assortment is a crucial mechanism for generating genetic diversity within populations. This diversity is the raw material for natural selection, allowing species to adapt and evolve in response to environmental changes. Without this genetic mix-and-match, offspring would be mere clones of their parents, limiting the potential for variation and hindering the evolutionary process.

What is a Phenotype?

In simple terms, a phenotype refers to the observable characteristics or traits of an organism. These are the physical, biochemical, and behavioral characteristics you can see or measure.

- Observable Traits: These traits are directly visible or measurable, such as height, eye color, blood type, and behavior.

- Genotype and Environment: A phenotype is determined by two main factors:

- Genotype: The organism’s genetic makeup (the specific alleles it carries).

- Environmental Factors: External influences like diet, temperature, or exposure to certain substances.

- examples physical form, developmental processes, biochemical and physiological properties, and products of behavior

Significance of Phenotype

Phenotypes are highly significant in biology and genetics for several reasons:

- Understanding Genetic Expression:

- Phenotypes allow us to observe the expression of an organism’s genes. The phenotype is the visible or measurable result of the genotype’s instructions.

- By studying phenotypes, we can begin to understand how specific genes contribute to particular traits.

- Studying Inheritance Patterns:

- Analyzing phenotypes (like in Punnett squares) helps us determine how traits are passed from one generation to the next.

- Phenotypic ratios (like the 9:3:3:1 ratio in a dihybrid cross) provide evidence for how genes are inherited.

- Evolutionary Studies:

- Natural selection acts on phenotypes. Organisms with phenotypes that are better suited to their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce.

- Changes in phenotypes over time are a key component of evolutionary processes.

- Medical and Agricultural Applications:

- In medicine, identifying specific phenotypes can help in diagnosing and treating diseases. For example, certain blood types are linked to certain medical conditions.

- In agriculture, selecting for desirable phenotypes (e.g., higher crop yield or disease resistance) is essential for breeding improved plants and animals.

- Phenotype studies in neuroscience:

- Refining phenotypes for the study of neuropsychiatric disorders is of paramount importance in neuroscience. Poor phenotype definition provides the greatest obstacle for making progress in disorders like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and autism.

- Without links from genome to multiple levels of phenomic data, advances in genetics will not be fully utilized. The challenge of finding genetic determinants for latent phenotypic constructs depends first on our ability to adequately define and refine these phenotypes.

Will the Phenotypic Ratio Remain Constant in the 3rd and 4th Generations?

The short answer is: It depends on the specific breeding scenario, but generally, the ratios will not remain exactly constant.

Here’s why:

- Statistical Nature: The phenotypic ratios (like 9:3:3:1) that we see in dihybrid crosses are probabilities based on large sample sizes. They represent the expected ratios in a population, not what will happen in every single family.

- Random Chance: Each mating event is unique. Even if the parents have the same genotypes as in the first generation, random chance plays a role in which alleles are passed on to the offspring.

- Sample Size: If you only look at a few offspring, the phenotypic ratios in that small sample might deviate significantly from the expected ratios. The ratios become more accurate when you look at many offspring.

- Deviation in subsequent generations: If we take the results of the F1 generation, and cross the organism obtained, the ratio will deviate from the ratio of the previous generation.

- New Combinations: In subsequent generations (3rd, 4th, etc.), if individuals with different genotypes are allowed to mate, new combinations of alleles and traits will emerge. This can lead to shifts in the overall phenotypic ratios compared to the initial cross.

- Environmental influence: Even if the genotype is the same, the expression of the genotype will be affected by environmental factors, leading to different phenotypes.

Summary

- Initial Ratios: In a basic dihybrid cross (e.g., PpTt x PpTt), the first generation (F1) will have a predictable phenotypic ratio (9:3:3:1) if the genes are unlinked.

- Subsequent Generations: In the 3rd, 4th, and later generations, the exact ratio will likely fluctuate due to statistical variations, random allele combinations, the effects of the environment, and the genotypes of the breeding pairs. The ratio will most likely deviate from the ratio observed in the F1 generation.

Beyond the Basics

While independent assortment is a fundamental principle, there are exceptions, such as when genes are located close together on the same chromosome (linkage). However, even linked genes can be separated through crossing over during meiosis, introducing further diversity.

In Conclusion

Independent assortment is a remarkable illustration of nature’s ingenuity. By allowing genes on different chromosomes to shuffle and recombine, it creates a vibrant tapestry of genetic possibilities, driving the diversity of life that surrounds us. This understanding deepens our appreciation for the elegant mechanisms that underpin heredity and the evolutionary journey of all living organisms.

Leave a comment