Table of Contents

- The Building Blocks: Basic Definitions

- Levels of Organization

- The Rules of the Game: Foundational Principles of Ecology

- An Organism’s “Job”: The Ecological Niche

- Where Worlds Collide: Ecotones, Ecoclines, and the Edge Effect

- The System of Life: Deconstructing the Ecosystem

- The Engine of Life: Functions of an Ecosystem

1. Forest Ecosystem Example

2. Etymology

3. Heterotroph Vs Phagotroph - Following the Energy: Food Chains, Food Webs, and the 10% Rule

- Types of Food Chains

- Food Web

- Ten Percent Law

- A Toxic Legacy: Pollutants in Ecosystems

1. Devastating effect of Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification - Nature’s Gifts: Ecosystem Goods and Services

- Measuring Life’s Engine: Ecosystem Productivity

- Conclusion

Have you ever wondered how a forest can sustain itself for thousands of years?

Or how a single drop of pond water teems with a universe of life?

The answers lie in Ecology, the intricate science that studies the web of relationships connecting all living things to each other and their environment.

Understanding ecology isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s fundamental to our survival. It teaches us how nature builds, sustains, and recycles, offering blueprints for a more sustainable human presence on Earth.

In this guide, we will journey through the foundational principles of ecology, starting with the basic building blocks and moving up to the complex dynamics that power our entire planet.

The Building Blocks: Basic Definitions

To understand the big picture, we must first learn the language of ecology. It all begins with a hierarchy of organization, like a set of Russian dolls, where each level is nested within the next.

Environment: This is the stage on which the drama of life unfolds. The environment is the sum of all external conditions—temperature, sunlight, water, soil, and other organisms—that influence an organism’s life and development.

Levels of Organization

- Organism: The starting point. An individual living being, whether it’s a single bacterium, a mushroom, or a blue whale.

- Population: A group of organisms of the same species living and interbreeding in the same area. Think of a herd of elephants in the Serengeti or all the sunflowers in a field.

- Community: All the different populations of various species interacting in a common location. The elephants, acacia trees, lions, and termites of the Serengeti together form a community.

- Ecosystem: This is where the living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) worlds formally meet. An ecosystem is a community of organisms interacting with their physical environment (like sunlight, soil, and water) as a complete system.

- Biosphere: The highest level of organization. The biosphere is the sum of all ecosystems on Earth—the part of our planet’s land, water, and atmosphere where life exists.

The Rules of the Game: Foundational Principles of Ecology

- Life is not static: it is a dynamic process shaped by a few powerful, underlying principles. These forces drive change, create diversity, and determine which organisms thrive.

- Adaptation: An organism’s key to survival. An adaptation is any inherited trait—be it morphological (a cactus’s spines), physiological (a camel’s ability to conserve water), or behavioral (birds migrating south for the winter)—that helps it survive and reproduce in its specific habitat.

- Variation: The raw material for change. These are the natural differences that exist between individuals of the same species. No two zebras have the exact same stripe pattern, just as no two humans are identical.

- Natural Selection: Nature’s quality control. This is the process where organisms with variations and adaptations better suited to their environment are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass those advantageous traits to their offspring.

- Evolution: The long-term result of natural selection. Evolution is the gradual change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations.

- Speciation: The birth of new species. This is the evolutionary process by which one population becomes so genetically different from its ancestors that it can no longer interbreed, forming a distinct new species.

- Coevolution: An evolutionary dance between species. This occurs when two or more species reciprocally influence each other’s evolution, like a flower and its specific pollinator, or a predator and its prey in a constant arms race.

- Extinction: The end of a lineage. This is the complete and permanent termination of a species when it can no longer adapt to changing environmental conditions or compete with other organisms.

An Organism’s “Job”: The Ecological Niche

Habitat Vs Ecological Niche:

If a habitat is an organism’s “address,” then its Ecological Niche is its “profession” and its role in the community.

Ecological Niche describes the unique functional role a species plays, encompassing everything it needs to survive (food, water, shelter) and its interactions with other species (predation, competition).

Types of Niches

- Fundamental Niche: This is the theoretical range of environmental conditions and resources an organism could potentially occupy and use if there were no competition or predators. It’s the ideal, unrestricted lifestyle.

- Realized Niche: This is the actual space and resources an organism uses in the real world. The realized niche is always smaller than the fundamental niche because it is limited by factors like competition with other species for food and territory.

Example:

- Habitat: A specific species of squirrel lives in an oak tree within a deciduous forest.

- Ecological Niche: The same squirrel’s niche involves burying acorns, which helps disperse tree seeds, and serving as prey for hawks.

- Fundamental Niche: The theoretical range where the squirrel could live includes the entire forest and surrounding area if no predators or other competing species were present.

- Realized Niche: In reality, the squirrel only occupies the lower branches of that one oak tree because other squirrels dominate the upper branches and hawks frequently hunt in the open field nearby.

Where Worlds Collide: Ecotones, Ecoclines, and the Edge Effect

Ecosystems rarely have sharp, defined borders.

Instead, they often blend into one another in fascinating ways.

- Ecotone: This is a transition area between two different biological communities, like the marshy zone between a lake and a forest, or the area where a grassland meets a desert.

- Edge Effect: Ecotones are often hotspots of biodiversity. The Edge Effect is the tendency for these junction zones to have a greater variety and density of species than either of the two flanking communities. This is because organisms from both ecosystems can live there, and unique species adapted to the edge conditions also thrive.

- Ecocline: Unlike the distinct (though blended) ecotone, an Ecocline is a gradual and continuous change in species composition along an environmental gradient. A classic example is the change in plant life as you move from the base of a mountain to its summit, with different species appearing as the temperature, soil, and exposure change.

Example:

- Ecotone: The salt marsh where a freshwater river meets the saltwater ocean is a distinct transition zone between two different ecosystems.

- Edge Effect: The border between a dense forest and a meadow is home to more species of birds, insects, and mammals than either the deep forest or the open meadow alone.

- Ecocline: As you hike up a mountain, you observe a gradual change in vegetation, from broadleaf trees at the bottom to conifers further up, and finally small, hardy alpine plants near the summit due to the continuous change in altitude and temperature.

The System of Life: Deconstructing the Ecosystem

An Ecosystem is the fundamental structural and functional unit of ecology. It’s a dynamic system where energy and nutrients are constantly flowing and cycling between its living and non-living components.

- Abiotic Components: The non-living chemical and physical parts of the environment, such as sunlight, temperature, water, atmospheric gases, soil, and nutrients.

- Biotic Components: The living parts of the ecosystem, which are organized by how they obtain energy

- Autotrophs (Producers): The foundation of every ecosystem. These organisms produce their own food from inorganic sources, primarily through photosynthesis (using sunlight). Plants, algae, and some bacteria are producers.

- Heterotrophs (Consumers): Organisms that get their energy by feeding on other organisms.

- Macroconsumers (Phagotrophs): These ingest other organisms. They include herbivores (plant-eaters), carnivores (meat-eaters), and omnivores (who eat both).

- Microconsumers (Saprotrophs/Decomposers): The unsung heroes of the ecosystem. Fungi and bacteria break down dead organic matter (like dead plants and animals) and waste products, returning essential nutrients to the soil for producers to use again.

Forest Ecosystem Example

- Abiotic Components: The non-living amount of sunlight determines how well plants can grow.

- Biotic Components: The collective living organisms—trees, deer, wolves, fungi—form the interactive community.

- Autotrophs (Producers): A fern converts sunlight into energy, forming the base of the food chain.

- Heterotrophs (Consumers): A deer eats the fern, and a wolf eats the deer, both relying on other organisms for energy.

- Macroconsumers (Phagotrophs): The deer and the wolf are large organisms that actively ingest their food (plants and meat).

- Microconsumers (Saprotrophs/Decomposers): Fungi and bacteria on the forest floor break down the waste and dead bodies of the trees, deer, and wolves, completing the cycle by returning nutrients to the soil.

Etymology

- Saprotroph: This term is a modern compound derived from two ancient Greek roots:

- sapros, meaning “rotten” or “putrid” .

- trophe, meaning “nourishment” or “food”.

- Thus, a saprotroph is an organism that obtains “rotten nourishment,” referring to its ability to feed on dead or decaying organic matter.

- Autotroph: This term is also derived from Greek roots:

- auto, meaning “self”.

- trophe, meaning “nourishment” or “food”.

- An autotroph, therefore, is a “self-nourisher,” capable of producing its own food, typically through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis.

- Heterotroph: This term combines two Greek elements:

- heteros, meaning “other” or “different .

- trophe, meaning “nourishment” or “food”.

- A heterotroph is an “other-nourisher,” meaning it obtains sustenance by consuming other organisms or organic substances.

- Phagotroph: This term is derived from two Greek components:

- phagein, a verb meaning “to eat” or “to devour”.

- trophe, meaning “nourishment” or “food”.

- A phagotroph is an “eating nourisher,” describing organisms that ingest whole particles or other organisms, often by engulfing them (phagocytosis).

Heterotroph Vs Phagotroph

The key difference is that heterotroph is a broad term for any organism that cannot produce its own food, while phagotroph refers to a specific method of heterotrophic nutrition involving the engulfment of solid food particles.

- Heterotrophs obtain organic nutrients by consuming other organisms or their organic matter. This general category includes various feeding strategies, such as:

- Phagotrophs: Organisms that ingest solid food, like animals eating plants or other animals, or an amoeba engulfing a bacterium.

- Saprotrophs/Osmotrophs: Organisms like fungi and some bacteria that secrete digestive enzymes externally onto dead or decaying matter and then absorb the dissolved nutrients.

- Parasites: Organisms that live on or inside a host and absorb nutrients from it.

- Phagotrophs (also called macroconsumers) are a type of heterotroph that specifically feed by ingesting or engulfing large food particles or whole organisms, which are then digested internally within their body or cells.

In essence, all phagotrophs are heterotrophs, but not all heterotrophs are phagotrophs (e.g., a fungus is a heterotroph, but an absorptive one, not a phagotroph).

The Engine of Life: Functions of an Ecosystem

Ecosystems are defined by four primary functions that keep them running:

1. Energy Flow: The one-way passage of energy through the ecosystem, typically from the sun to producers and then through various consumers.

2. Nutrient Cycling (Biogeochemical Cycles): The continuous movement of essential elements (like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus) from the physical environment into living organisms and back again.

3. Ecological Succession: The gradual and predictable process of change in an ecosystem’s species structure over time, such as a field turning into a forest.

4. Homeostasis (Ecosystem Regulation): The ability of an ecosystem to maintain a state of equilibrium and self-regulate through feedback mechanisms, resisting change and ensuring stability.

Following the Energy: Food Chains, Food Webs, and the 10% Rule

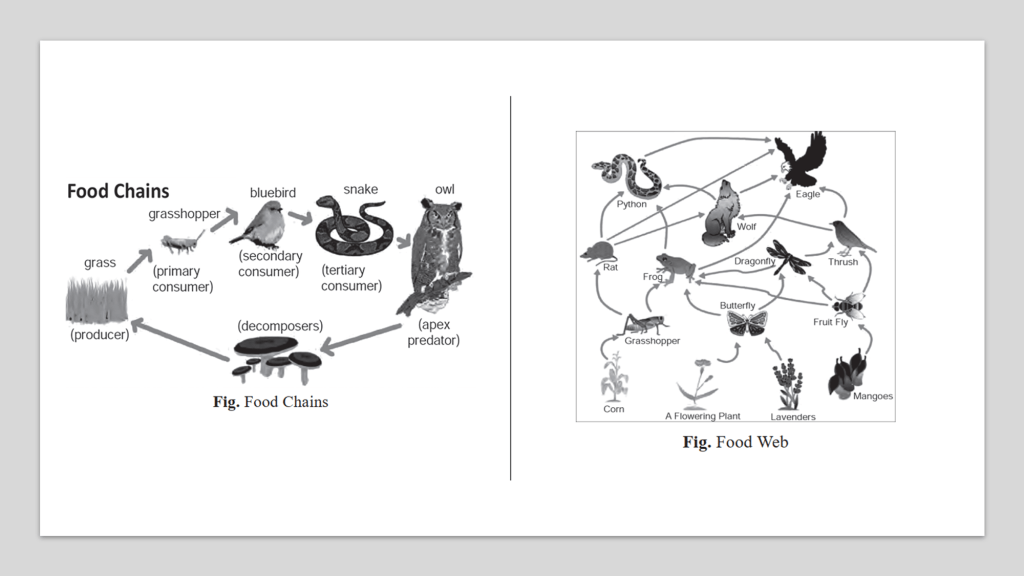

The transfer of food energy from producers through a series of organisms is called a Food Chain.

Each step in this chain is a Trophic Level.

Types of Food Chains

- Grazing Food Chain: The classic model that starts with green plants (producers), moves to herbivores (primary consumers), and then to carnivores (secondary and tertiary consumers).

- Detritus Food Chain: This chain begins with dead organic matter (detritus), which is consumed by decomposers and detritivores (like earthworms and fungi), who are then eaten by other organisms.

| Basis of Difference | Grazing Food Chain | Detritus Food Chain |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Energy Source | Solar energy, captured by living plants via photosynthesis. | Dead organic matter (detritus), such as dead leaves, wood, and animal remains. |

| Starts with | Living green plants (producers). | Dead organic matter/detritus. |

| First Trophic Level | Herbivores (primary consumers) that feed on living plants. | Detritivores and decomposers (e.g., bacteria, fungi, earthworms) that feed on dead matter. |

| Main Organisms Involved | Typically involves macroscopic organisms (plants, large animals). | Dominated by microscopic organisms (bacteria, fungi) and smaller detritivores (e.g., worms). |

| Primary Role | The initial flow and transfer of energy into the ecosystem. | Recycling nutrients by breaking down dead matter and returning them to the soil. |

| Energy Flow | Generally a larger, more complex food chain with more trophic levels. | Generally a smaller food chain with fewer trophic levels. |

| Dominant Ecosystem | Major energy flow in aquatic ecosystems (phytoplankton → fish). | Major energy flow in terrestrial ecosystems like forests, where a large fraction of plant biomass dies without being eaten by herbivores. |

| Example | Grass → Rabbit → Fox | Dead leaves → Earthworm → Bird |

In reality, ecosystems are more complex than a single chain.

Food Web

A Food Web is a much more accurate model, representing a complex network of interconnected food chains that shows all the feeding relationships in a community.

| Basis of Difference | Food Chain | Food Web |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | A simple, linear (straight-line) sequence of energy transfer. | A complex, intricate network of interwoven food chains. |

| Energy Pathways | Energy flows along a single, direct path (e.g., Grass → Rabbit → Fox). | Energy flows through multiple, overlapping pathways, reflecting diverse feeding choices. |

| Realism | A simplified, often hypothetical model of energy flow, rarely found in isolation in nature. | A more realistic and accurate representation of actual feeding relationships in an ecosystem. |

| Organism’s Diet | Organisms at higher trophic levels often feed on only one specific species of organism below them in the chain. | An organism can have multiple food sources and be eaten by several different predators. |

| Ecosystem Stability | Less stable; if one organism is removed, the entire chain is severely disrupted. | More stable and resilient; the removal of one organism does not collapse the whole system because alternatives exist. |

| Example | Grass → Deer → Wolf | Plants are eaten by rabbits and mice; both rabbits and mice are eaten by owls and snakes; owls can also eat snakes, creating a complex web of interactions. |

Ten Percent Law

A critical principle governing this energy flow is the Ten Percent Law.

This rule states that when energy is transferred from one trophic level to the next, only about 10% of it is converted into new biomass. The remaining 90% is lost as heat during metabolic processes, used for movement, or is simply not consumed.

This is why food chains rarely have more than four or five levels—there simply isn’t enough energy left at the top.

A Toxic Legacy: Pollutants in Ecosystems

The structure of the food chain has serious implications for the movement of pollutants.

- Bioaccumulation: This is the buildup of a substance, such as a pesticide or heavy metal, in the tissues of a single organism over its lifetime because the organism absorbs it faster than it can remove it.

- Biomagnification (or Bioamplification): This is the more dangerous process where the concentration of a toxin increases at successively higher trophic levels in a food chain. For example, a small amount of a pollutant in plankton is eaten by many small fish. A larger fish eats many of those small fish, accumulating the toxin from all of them. Finally, a bird of prey eats several of those larger fish, receiving a highly concentrated, often lethal, dose.

Devastating effect of Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification

1. Concentration from Low Levels: The process begins with persistent toxins (pollutants that don’t break down easily) entering the environment, often at very low and seemingly harmless concentrations. Through Bioaccumulation, an organism absorbs these toxins faster than it can get rid of them, causing the pollutant to build up in its tissues over its lifetime. This turns a single, long-lived organism into a small reservoir of concentrated toxins.

2. Amplification Up the Food Chain: Biomagnification takes this individual problem and makes it an ecosystem-wide threat. When a predator eats contaminated prey, it ingests and retains the toxins from that prey. Since a predator consumes many prey items, the toxins from all of them are concentrated into that single predator’s body. This process is repeated at each level, causing the toxin’s concentration to become exponentially higher as it moves up the food chain.

For instance, DDT pesticide magnifies at each level until its breakdown product, DDE, inhibits calcium deposition and causes fatal eggshell thinning in birds of prey like bald eagles.

The role of the bald eagles is to serve as the top predators at the highest level of the food chain, illustrating the most severe impact of the biomagnification process.

3. Disruption at the Top (Trophic Cascade): The greatest danger is that the highest, most lethal concentrations of toxins end up in the apex predators. These top-level carnivores are often keystone species that regulate the populations of other animals and maintain ecosystem stability. The toxins cause severe health effects like reproductive failure (DDT and bird eggs), neurological damage, and weakened immune systems, leading to a decline in their populations. The loss of these top predators can trigger a trophic cascade, causing the entire food web below them to become unbalanced and unstable.

Nature’s Gifts: Ecosystem Goods and Services

Healthy ecosystems provide humanity with essential resources for survival and well-being.

- Ecosystem Goods: These are the tangible, material products we obtain from ecosystems. This includes food (fish, fruits), raw materials (timber, fuel), fresh water, and medicinal plants.

- Ecosystem Services: These are the critical benefits provided by the proper functioning of ecosystems. These services often go unnoticed but are priceless. They include air and water purification, climate regulation, pollination of crops, soil formation, and nutrient cycling.

Measuring Life’s Engine: Ecosystem Productivity

Productivity: Productivity is the rate at which biomass (the mass of living organisms) is generated in an ecosystem. It’s a measure of the ecosystem’s energy-capturing efficiency.

- Primary Productivity: This refers to the rate at which producers like plants create biomass from inorganic sources.

-> Gross Primary Productivity (GPP): The total rate of energy captured by photosynthesis. It’s the entire energy “paycheck” an ecosystem’s producers earn.

-> Net Primary Productivity (NPP): This is the energy that remains after producers use some of it for their own respiration (R). NPP = GPP – R. NPP represents the total biomass available to be consumed by herbivores and decomposers—it’s the energy that powers the rest of the food web. - Secondary Productivity: This is the rate at which consumers (herbivores, carnivores) convert the energy from the food they eat into their own new biomass.

- Net Ecosystem Productivity (NEP): This measures the total rate of organic matter accumulation for the entire ecosystem. It accounts for the respiration of all organisms, both producers and consumers, and gives us a picture of whether the ecosystem is gaining or losing carbon over time.

Example:

- Productivity is the general concept of how fast an ecosystem generates living matter (biomass), like how a coral reef has a high rate of biomass generation.

- Primary Productivity is a type of productivity specifically focused on the very start of the food chain—the rate at which producers (like the algae in a pond) create this biomass using photosynthesis.

- Gross Primary Productivity (GPP) is a measurement of primary productivity that represents the total raw energy captured before the producer uses any of it for itself, such as when a forest’s trees convert a full 10,000 kilocalories of solar energy into organic matter per day.

- Net Primary Productivity (NPP): After using 2,000 kilocalories for their own respiration, the trees in that forest have 8,000 kilocalories of energy available for herbivores.

- Secondary Productivity: The rate at which a population of rabbits converts the grass they eat into their own body mass.

- Net Ecosystem Productivity (NEP): A young, growing forest has a positive NEP, meaning it is accumulating more carbon over time than is being released by the respiration of all its organisms.

Conclusion

An Interconnected World

- From a single organism adapting to its surroundings to the global flow of energy that connects us all, the principles of ecology reveal a world of profound interconnectedness.

- Every component, living and non-living, plays a crucial role.

By understanding these foundational concepts—from the niche of a single species to the productivity of an entire ecosystem—we not only deepen our appreciation for the natural world but also gain the knowledge necessary to protect it for generations to come.

Leave a comment