- Doppler Effect Overview

- Classical Doppler Effect

- Formula for Classical Doppler Effect

- Relativistic Doppler Effect

- Formula for Relativistic Doppler Effect

- Classical Doppler Effect

- Key Differences Between Classical and Relativistic Doppler Effects

- Velocity Regime

- Type of Waves

- Relativistic Corrections

- Observed Frequency

- Use Case

- Frequency Shift (Significance of Speed)

- Effect on Wave Wavelength

- Observed in Different Media

- Summary of Differences – Tabular Comparison

- Wavefronts and Relativistic Doppler Effect

- The Doppler Effect: Star Moving Towards the Observer

- Relating it to the Color of Light (Blueshift)

- The Doppler Effect: Star Moving Away from the Observer

- Relating it to the Color of Light (Redshift)

- Relativistic Effects

- Summary

- The Doppler Effect: Star Moving Towards the Observer

- Time Dilation and the Relativistic Doppler Effect

- The Doppler Illusion: Does Wavelength Really Change

- What do we actually observe

- Here’s why we don’t directly perceive the complete sine wave

- Summary

- The Actual Wavelength vs. the Observed Wavelength

- How Wavefront Bunching Creates the Illusion of Decreased Wavelength

- Analogy

- Summary

- What do we actually observe

Doppler Effect Overview

The Doppler Effect refers to the change in the frequency or wavelength of a wave as observed by someone moving relative to the source of the wave. This effect is commonly experienced with sound waves, but it also applies to electromagnetic waves like light. Essentially, the observed frequency increases when the source moves toward the observer and decreases when it moves away from the observer.

Classical Doppler Effect

The Classical Doppler Effect refers to the change in frequency or wavelength that occurs due to the relative motion of a sound source and an observer, under the assumption that the source and the observer are moving at speeds much lower than the speed of light. It applies to situations where the velocities involved are not relativistic (i.e., far less than the speed of light).

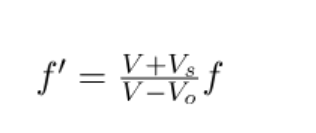

Formula for Classical Doppler Effect

The general formula for the classical Doppler effect for sound is:

Where:

- ( f’ ) is the observed frequency.

- ( f ) is the emitted frequency.

- ( v ) is the speed of sound in the medium.

- ( v_o ) is the speed of the observer.

- ( v_s ) is the speed of the source.

- The signs depend on whether the observer and source are moving toward or away from each other.

- If the observer is moving toward the source, use the ( + v_o ) term in the numerator (observer moving towards increases frequency).

- If the observer is moving away from the source, use the ( – v_o ) term (observer moving away decreases frequency).

- If the source is moving toward the observer, use the ( – v_s ) term (source moving towards increases frequency).

- If the source is moving away from the observer, use the ( + v_s ) term (source moving away decreases frequency).

Relativistic Doppler Effect

The Relativistic Doppler Effect applies when the relative speed between the observer and the source is a significant fraction of the speed of light, and thus special relativity must be considered. This formula takes into account the time dilation and the fact that the speed of light is constant in all inertial reference frames.

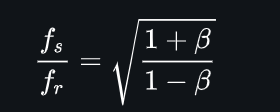

Formula for Relativistic Doppler Effect

For light or electromagnetic waves, the relativistic Doppler effect is given by:

Where:

- ( f’ ) is the observed frequency.

- ( f ) is the emitted frequency.

- beta = v/c , where ( v ) is the relative speed between the source and observer, and ( c ) is the speed of light.

- The observed frequency increases if the source and observer are moving toward each other, and decreases if they are moving apart.

Key Differences Between Classical and Relativistic Doppler Effects

Velocity Regime

- Classical Doppler Effect: Applies to situations where the relative velocity between the source and observer is much smaller than the speed of light (non-relativistic speeds). It is typically used in everyday scenarios like sound waves.

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: Applies when the relative velocity is a significant fraction of the speed of light (relativistic speeds). It is used when objects move close to the speed of light or in high-energy physics and astronomy.

Type of Waves

- Classical Doppler Effect: Generally used for sound waves or any other waves in a medium (like water waves), where the wave speed is finite and the relative velocities are low.

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: Primarily used for electromagnetic waves (light, radio waves, etc.), where the speed of light (c) is the wave speed, and relativistic effects become significant at high velocities.

Relativistic Corrections

- Classical Doppler Effect: Does not account for relativistic effects like time dilation or length contraction. It assumes a linear relationship between velocity and frequency shift.

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: Incorporates relativistic effects such as time dilation, which causes the observed frequency shift to not be linear at high velocities. The frequency shift depends on the Lorentz factor.

Observed Frequency

- Classical Doppler Effect: The observed frequency shifts linearly with the relative speed of the source and observer. The shift is more intuitive (the faster the motion, the greater the frequency shift).

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: The observed frequency shifts in a more complex, non-linear way, especially at velocities close to the speed of light. The frequency shift is dependent on the Lorentz factor.

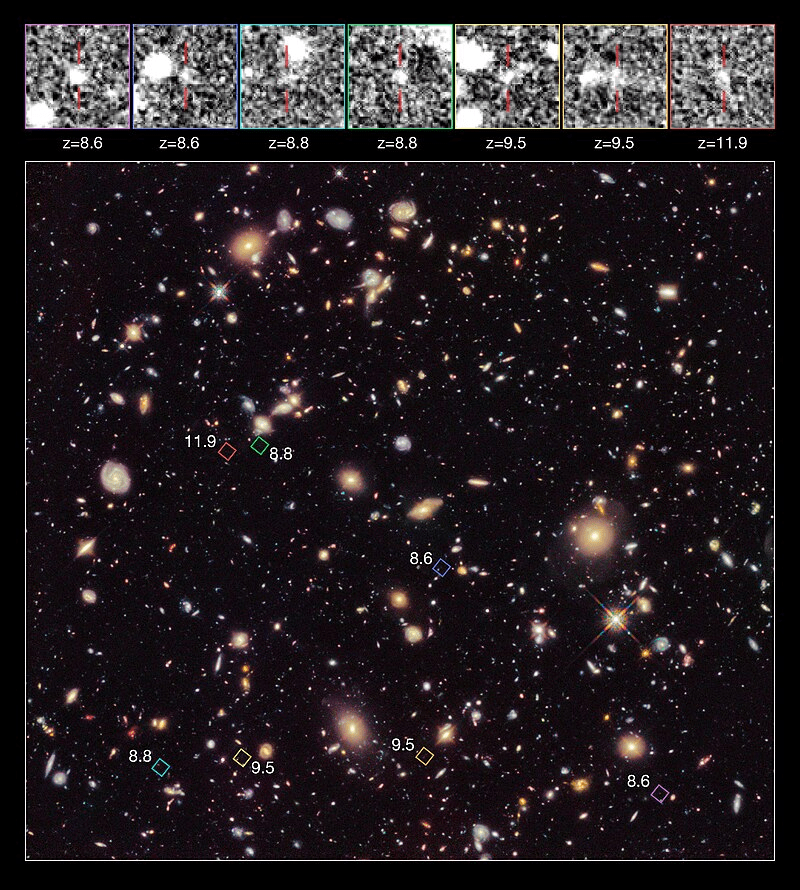

Use Case

- Classical Doppler Effect: Used in everyday, low-velocity situations, like sound waves from a moving vehicle or train, or waves in water.

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: Used in high-velocity scenarios involving light, such as redshift or blueshift observed in astronomy (e.g., the motion of stars or galaxies) or in high-energy particle physics.

Frequency Shift (Significance of Speed)

- Classical Doppler Effect: The frequency shift is directly proportional to the relative velocity. As the velocity increases, the frequency shift increases linearly.

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: The frequency shift becomes more pronounced as the relative velocity approaches the speed of light, but due to the nature of relativity, the shift grows at a slower rate compared to classical expectations.

Effect on Wave Wavelength

- Classical Doppler Effect: The wavelength of the wave changes in proportion to the change in observed frequency. The wavelength shortens if the source and observer are moving toward each other, and lengthens if moving apart.

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: The change in wavelength is also affected by relativistic time dilation and length contraction. The wavelength shift is tied to the observed frequency change but is subject to relativistic corrections.

Observed in Different Media

- Classical Doppler Effect: Typically observed in a medium (like air for sound, water for waves). The velocity of the medium is important (e.g., sound waves travel at different speeds in air, water, or steel).

- Relativistic Doppler Effect: Occurs for electromagnetic waves (light, radio, etc.), and is not dependent on a medium. The speed of light is constant in all inertial reference frames.

Summary of Differences – Tabular Comparison

| Aspect | Classical Doppler Effect | Relativistic Doppler Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity Range | Low velocities (much slower than the speed of light) | High velocities (close to the speed of light) |

| Used For | Sound waves, everyday objects | Electromagnetic waves (light, radio, etc.) |

| Formula | ( f’ = f \left( \frac{v \pm v_o}{v \mp v_s} \right) ) | ( f’ = f \sqrt{\frac{1 – \beta^2}{1 + \beta^2}} ) |

| Relativistic Effects | Not included (no time dilation) | Included (time dilation affects frequency shift) |

| Frequency Shift | Linear with relative speed | Non-linear with relative speed, involving Lorentz factor |

| Application | Everyday situations (e.g., sound from moving vehicles) | High-speed scenarios (e.g., redshift in astronomy) |

| Effect on Wavelength | Linear change in wavelength | Relativistic effects modify wavelength shift as well |

| Speed Limit | No upper limit for speed (but limited by medium properties) | Limited to the speed of light |

| Medium Required | Medium is required for Waves to travel | No Medium required since we deal with EM waves |

The Classical Doppler Effect is suitable for everyday low-speed scenarios (like the sound of a passing car), while the Relativistic Doppler Effect is necessary for high-speed, relativistic situations (like the redshift of galaxies or high-velocity particles).

The key difference lies in the need for relativistic corrections when dealing with speeds close to the speed of light.

Wavefronts and Relativistic Doppler Effect

Imagine a star emitting light waves.

- Wavefronts: These are the crests of the light waves, representing points where the electromagnetic field is at its maximum at a given moment. The wavefronts are the locations where the wave reaches the same phase at any given moment. They spread out from the star in a spherical pattern.

- Wavelength: The distance between two consecutive wavefronts (crests) is called the wavelength. It’s the distance between two peaks of the electromagnetic wave.

- Frequency: The number of wavefronts (crests) passing a fixed point per unit of time is the frequency. It’s how many wave crests of light pass a specific point in space in one second.

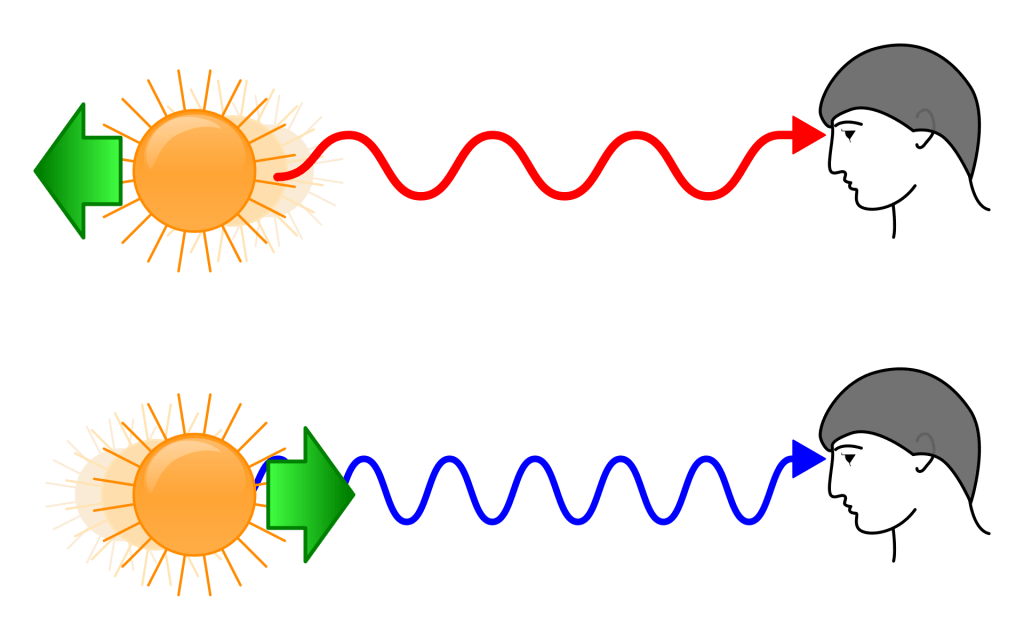

The Doppler Effect: Star Moving Towards the Observer

Now, imagine the star (light source) moving towards you (the observer) at a significant speed.

- Wavefront Bunching: As the star moves closer, it emits new wavefronts from a position closer to the previous ones. This causes the wavefronts in front of the star to get compressed or “bunched up.”

- Effect on Wavelength: Because the wavefronts are closer together, the wavelength of the light decreases. The distance between consecutive wave crests becomes shorter.

- Effect on Frequency: Since the wavefronts are bunched up, more wave crests pass a fixed point in space in the same amount of time. This means the frequency of the light increases. The observer detects light waves more frequently as the star approaches.

Relating it to the Color of Light (Blueshift)

In the case of light, a decrease in wavelength and an increase in frequency cause a shift towards the blue end of the electromagnetic spectrum. This is called a blueshift. The star’s light appears bluer than it would if it were stationary.

The Doppler Effect: Star Moving Away from the Observer

If the star were moving away from you, the opposite would happen:

- Wavefront Spreading: The wavefronts would spread out, becoming further apart.

- Effect on Wavelength: The wavelength would increase, as the distance between wave crests becomes longer.

- Effect on Frequency: Fewer wave crests would pass a fixed point in the same amount of time, resulting in a decrease in the frequency of the light.

Relating it to the Color of Light (Redshift)

In this case, the increase in wavelength and decrease in frequency cause a shift towards the red end of the electromagnetic spectrum. This is called a redshift. The star’s light appears redder than it would if it were stationary.

Relativistic Effects

For light, the relativistic Doppler effect also plays a role, especially at high speeds.

Time Dilation: As the source moves faster, time dilation causes the emitted waves to appear to be emitted at a slower rate from the observer’s perspective. This further compresses the wavefronts for an approaching source and stretches them for a receding source.

Lorentz Transformation: The relativistic Doppler effect is governed by the Lorentz transformation, which describes how space and time are perceived differently by observers in relative motion. This transformation also affects the wavelength and frequency of the light, contributing to the observed blueshift or redshift.

Summary

- Wavefronts: Crests of the light waves.

- Wavelength: Distance between consecutive wavefronts.

- Frequency: Number of wavefronts passing a point per unit of time.

- Relativistic Doppler Effect (Star Moving Towards Observer): Wavefronts bunch up, wavelength decreases, frequency increases (blueshift).

- Relativistic Doppler Effect (Star Moving Away from Observer): Wavefronts spread out, wavelength increases, frequency decreases (redshift).

- Source moving towards observer: Light waves appear compressed (blueshift).

- Source moving away from observer: Light waves appear stretched (redshift).

These changes in wavelength and frequency are due to the relative motion between the source and the observer, and they are key to understanding various phenomena in astronomy and physics.

Time Dilation and the Relativistic Doppler Effect

If you want to know more about Time Dilation, you can go here:

The Time Dilation Enigma: How the Fabric of Time Can Stretch and Shrink

According to special relativity, time dilation occurs when an object moves at a significant fraction of the speed of light relative to an observer. This causes time to appear to pass more slowly for the moving object relative to the stationary observer.

Now, let’s consider a light source moving relative to an observer. From the observer’s perspective, the light source is moving, and time dilation occurs. As a result, the frequency of light emitted by the source appears to change.

Imagine two observers, Alice and Bob. Alice is moving relative to Bob at a significant fraction of the speed of light. Both observers have identical clocks, which they synchronize before Alice starts moving.

As Alice moves, her clock appears to run slower relative to Bob’s clock due to time dilation. Now, imagine that Alice emits a light pulse at a frequency of 100 Hz (according to her clock). From Bob’s perspective, the frequency of the light pulse will appear to be different due to time dilation.

Since Alice’s clock is running slower, the time between successive peaks of the light wave will appear longer to Bob. As a result, the frequency of the light pulse will appear to be lower to Bob. This is the Relativistic Doppler Effect.

Mathematical Formulation

The Relativistic Doppler Effect can be mathematically formulated using the Lorentz transformation. The frequency of light emitted by a moving source is given by:

f’ = f * sqrt((1 – v/c) / (1 + v/c))

where f’ is the observed frequency, f is the emitted frequency, v is the relative velocity, and c is the speed of light.

This equation shows that the observed frequency is dependent on the relative velocity and the emitted frequency. When the relative velocity is significant, the observed frequency can be substantially different from the emitted frequency.

In conclusion, the Relativistic Doppler Effect is a fundamental consequence of special relativity, arising from the interplay between relative motion and time dilation. This effect has been experimentally confirmed and has important implications for our understanding of the universe, particularly in the context of high-energy astrophysics and cosmology.

The Doppler Illusion: Does Wavelength Really Change

What do we actually observe

When we observe light from a source, our detectors (including our eyes) primarily register the intensity of the light over time (which represents the electromagnetic wave’s oscillations). Intensity is a measure of the energy carried by the light wave.

Here’s why we don’t directly perceive the complete sine wave

- High Frequency of Oscillations: Light waves oscillate at extremely high frequencies (hundreds of terahertz). Our eyes and typical instruments cannot respond fast enough to capture these rapid oscillations.

- Intensity as an Average: Instead, we detect the time-averaged intensity of the light. This is analogous to perceiving the overall brightness of a light source, rather than seeing the individual fluctuations of the electromagnetic field.

- Wavefronts and Intensity: The intensity peaks we detect can be thought of as representing the wavefronts or the points of maximum energy in the electromagnetic wave.

- Flicker of Intensities: Our perception of light is essentially a series of these intensity peaks arriving successively, creating a sensation of continuous light.

- Wavelength: The time interval between these successive intensity peaks (wavefronts) is related to the wavelength of the light.

Summary

Light is an electromagnetic wave with rapid oscillations, but human vision and instruments like telescopes and spectrometers can’t directly detect these oscillations. Instead, they measure the intensity of light, which represents the energy carried by the wave. Due to the high frequency of light oscillations (e.g., 500 trillion times per second), instruments average the signal over time, smoothing out the oscillations and providing a steady signal of intensity. This allows us to observe the overall energy of the light, but not its exact oscillatory pattern.

In summary: We don’t directly observe the complete sine wave of an incoming electromagnetic wave. We detect a sequence of intensity peaks, which are analogous to wavefronts. The time between these peaks is related to the wavelength of the light.

The Actual Wavelength vs. the Observed Wavelength

It’s crucial to distinguish between the actual wavelength of the emitted waves and the wavelength that is perceived by the observer due to the Doppler effect.

- Actual Wavelength: The actual wavelength of the light emitted by the source does not change due to the source’s motion. This is a fundamental property of the wave itself, determined by the source’s internal processes.

- Observed Wavelength: However, the observer perceives a change in wavelength due to the relative motion between the source and the observer. This perceived change is a consequence of the wavefronts bunching together (or spreading out) as the source moves.

When the source is moving towards the observer, it’s emitting wavefronts that are “bunched up” due to its motion.

Imagine ripples in water caused by a source, like a stone thrown into a pond.

Each ripple represents a wavefront, and every wavefront has its own unique wavelength and frequency. Each wavefront has its own wavelength, which is the distance between consecutive peaks or troughs of that particular wavefront. Let’s call this wavelength “λ” (lambda).

The distance between two consecutive ripples, or wavefronts, is considered one wavelength

Now, when the observer is watching the successive wavefronts emitted by the moving source, they’re not directly observing the wavelength of each individual wavefront. Instead, they’re observing the distance between successive wavefronts.

This distance between successive wavefronts is what we’re calling the “apparent wavelength” or “observed wavelength”. Let’s call this wavelength “λ_obs” (lambda observed).

The key point is that λ_obs is not the same as λ, the wavelength of each individual wavefront. λ_obs is the distance between successive wavefronts, which is affected by the motion of the source.

In this case, since the source is moving towards the observer, the wavefronts are “bunched up”, and the distance between successive wavefronts (λ_obs) appears shorter than the wavelength of each individual wavefront (λ).

So, when we say that the wavelength appears shorter, we’re referring to λ_obs, the observed wavelength, which is the distance between successive wavefronts. Each individual wavefront still has its own wavelength, λ, but the observer is seeing the effects of the source’s motion on the distance between successive wavefronts.

How Wavefront Bunching Creates the Illusion of Decreased Wavelength

Here’s how wavefront bunching creates the illusion of a decreased wavelength:

- Source at Rest: When the source is stationary, the observer receives wavefronts (crests) at regular intervals, corresponding to the actual wavelength of the emitted waves.

- Source Moving Towards Observer: As the source moves towards the observer, each successive wavefront is emitted from a position closer to the observer than the previous one. This causes the wavefronts to bunch up in front of the source.

- Perceived Wavelength: The observer now receives wavefronts more frequently than they would if the source were stationary. This increased frequency of wavefront arrival creates the perception that the distance between wavefronts (the wavelength) has decreased.

We perceive these wavefronts as light intensities. Therefore, when the wavefronts bunch together due to the source’s motion, the time interval between successive light intensities decreases. This decrease in duration is interpreted as a decrease in wavelength and a corresponding increase in frequency, resulting in the blue shift phenomenon.

It’s important to emphasize that this decrease in wavelength is an apparent effect, not a change in the actual wavelength of the emitted waves.

Analogy

Think of a person throwing balls towards you at regular intervals. If the person is stationary, you’ll catch the balls at the same rate they are thrown. But if the person starts walking towards you while throwing, you’ll catch the balls more frequently, even though the person is still throwing them at the same rate. This increased frequency of catching the balls gives you the impression that the distance between the balls (analogous to wavelength) has decreased.

Summary

- The actual wavelength of the emitted waves remains constant.

- Wavefront bunching due to the source’s motion causes the observer to receive wavefronts more frequently.

- This increased frequency creates the perception that the wavelength has decreased, even though it hasn’t changed in reality.

The Relativistic Doppler effect is primarily about the change in the perceived frequency and wavelength due to the relative motion between the source and the observer. The actual properties of the waves themselves (like their inherent wavelength) remain unchanged.

Leave a comment